Life In San Francisco

Christopher Owens on JR White, the decimation of the San Francisco scene, and Girls

Last month, I sat down with Christopher Owens at Orphan Andy’s to discuss love, life in San Francisco, and of course, Girls. Chris was warm and real, and our conversation covered so much ground that I wanted to give it a second life here in print. If you’d prefer, you can listen to the full episode here.

This interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

You’re planning to leave San Francisco.

Yeah, it’s crazy.

And you’re headed to New York?

Yep. You couldn’t go farther away if you tried—in America anyway. But I can say with full conviction that I tried my hardest to stay here.

To stay in San Francisco, you mean?

Yeah. Nobody can call me a ship-jumper or anything like that. It was seven or eight years ago when Thee Oh Sees left and Ty Segall left. Everybody was just leaving, and I was pretty vocal about how that was a bad idea and how I’d never do that.

You’ve stuck it out.

Yeah. I’ve just reached a point where I can’t do it anymore. So it’s gotta be done.

You’ve been here since 2005. How would you characterize the difference in the city today versus when you showed up?

When I showed up, I was coming from the Texas plains. Flat cattle grazing land, nothing for miles. There were neighbor cities called like, “Plainview.” So the first thing that struck me was how beautiful San Francisco was. And obviously it still is. It’s a hell of a city. But the thing that really hooked me… Like, I got here and I used to just walk around taking pictures of people’s gardens and flowers and nature, the hills. It was like night and day from Texas. But even with all that, after six months I started having a breakdown, because I hadn’t met anybody. I was riding the train an hour and a half to and an hour and a half from work.

You were commuting out of the city?

Yeah, out and back to San Mateo. I would read, it was fine. But I would go to this one bookstore in my neighborhood that had free jazz concerts, and I loved it. It was amazing—it was a tiny little bookstore, and every Friday night they’d have these old jazz guys come and play standards. It was a lovely thing.

But I found that and not much else. I would go through The San Francisco Bay Guardian and go to everything I saw that looked cool or interesting or was free, and it was all a strikeout. I hated this, I hated that. I was starting to feel like I might’ve put too much faith in the big city, because I thought I was coming somewhere to find everything I was missing in Amarillo. I was ready to leave.

But then I met this girl, Liza, and the group of people that would become my friends. And overnight I came into the scene that I would hang out in for the next ten or fifteen years. And that really is what kept me here. That was amazing. You couldn’t walk through the Mission for more than three blocks in an evening without finding a house party. You’d run into somebody every time you went to get a coffee and find out about something to do. There were shows all the time, bands everywhere…

It was a little community, a little village.

People were hungry and interested and driven to hang out with each other and find the things in life that can’t be found through getting a good job and having money in the bank.

When Girls happened, that was probably the peak of that scene here, and it was nothing but great people. I probably had three hundred great friends, which sounds crazy to say, but it really was like that. And we did nothing but spend time with each other, all the time. It was like paradise for me.

That was 2008, 2009?

Yeah, or even earlier. 2007.

Because you were in Holy Shit until 2006 or 2007, right?

I was in Holy Shit until probably about 2008. It was before and during the beginning of Girls.

We didn’t get our first record finished and sign our deal until 2009, so there was a year or two where we were playing here in San Francisco. It was a thing in California, but we hadn’t really gotten off the ground yet.

I remember the first time I saw you was at the El Rey opening for Los Campesinos.

I remember that show, yeah! That was our first big US tour. They were label mates from our UK label.

It was an amazing show. I had zero idea about who you guys were, and you just fucking blew my mind.

I totally remember that show. I took a Polaroid picture with one of the girls from Los Campesinos, the violin player. She was a babe. And I looked like a ragamuffin, like a skinny Chucky doll with cowboy boots. And she’s like this great European girl with a violin. It was a cool show.

That whole tour was really cool, because I’d never done anything like that. That was our first US tour, and I hadn’t experienced the fans, the kids that would show up. And that never really went away.

I saw you guys ten or fifteen times in those couple years, and every show—from opening for Los Campesinos to playing FYF—everyone was just in love with you guys.

FYF was amazing. I remember that, that was our first sunset festival slot. Up until then we’d only played in the sunlight.

Once the sun starts going down while you’re playing, that’s when you know you’re making it.

Yeah. And we had the girls, the backup singers with us.

With the bouquets on the mic stands.

That was the first home run festival show for us.

But as for people leaving San Francisco—the big thing that happened was the mayor at the time, Ed Lee, decided to give tech companies four years of tax breaks if they would move their offices here. So of course the companies took that: four years of tax breaks for companies that size is a huge, huge deal.

The results were catastrophic. Twitter set up in that building down on Market, and everybody followed, and all of a sudden they’re hiring the country’s smartest college graduates. And these guys don’t fuck around. They’re buying houses, places where twenty of us lived before. And they’re buying it for one or two people. That just starts happening really fast. So there are fewer places on the market to rent, and prices are doubling and doubling. Within a year, Bottom of the Hill has to relocate because the noise is bothering people that’ve recently bought nearby properties. All kinds of venues were shutting down. And basically every time I would see someone it was like, “Oh yeah, I’ve gotta get outta here, I can’t afford to live here.”

People were just running as fast as they could to LA or Austin or New York. My reaction was like, “Don’t, please don’t.” I loved what we had, and I knew if people left it would just die. And everybody was like, “New people will come here,” and I thought maybe that was true. But it wasn’t the same. We’re talking about my best friends, people I really really really really loved. It was really hard to see them go. But I was protected, because I lived in the same place for a long time with my girlfriend, and our rent was still cheap.

What neighborhood were you in?

The Haight, by Golden Gate Park, the Panhandle. It just very quickly changed. And by the time I had a reality check, when I suddenly had to vacate the apartment and try to find a new place to rent, and look around at who was still here, and not just spend time with my girlfriend all the time—we split up—hardly anybody was here, and I couldn’t afford to rent anywhere. I found one place that I lived in for six months and then I was out of money.

So after two years of that, I had zero friends here. So the difference for me is total. I still love the city like I did when I moved here, it’s still one of the best places you could ever live. But it’s populated with people who pursue the standards—house, money, marriage—above all else. If you’re not doing that here, you might not be able to make it anymore, because that’s your competition.

As a byproduct of that, now you’ve also got all these people here who’ve grown up in very different neighborhoods. They’ve never seen some of the things that happen on the street here, and they’re scared. They come here from whatever bubble they were in, and they’ve gotten a great salary, and they’ve got horse blinders on. And any little schmo coming in from the side is just a threat. Before, you could go out to the coffee shop and get your coffee and stand around outside and smoke. Now you’re gonna have someone come and tell you to stop smoking because they can smell it in their place, or ask you to go somewhere else.

If you look like me… I mean, people call the police on me, people assume crazy things. I walked into the Levi’s store, where they’ve been using my music to sell their jeans, and this guy is like, “Get out, we don’t want any trouble in here.” And I’m like, “What the fuck are you talking about?” I’m not trouble, I’m a superhero here. I achieved the American Dream here. I’m James Dean in Giant, I struck oil here. I’m the man. And you’re telling me to get out?

It just started happening everywhere. It shocked me at first, but it doesn’t anymore. So the change is total. Out with your friends, in with a new group of people that doesn’t understand you and is very suspicious of you. It’s just been chaos.

But I refuse to change who I am. I don’t go out of my way to look dirty, I just look how I look. And to most people that makes me a homeless junkie. They’ll cross the street while you’re walking towards them, or lock their car when you walk next to it. When ladies started to cross the street rather than pass me, or move their purse to the other side of their body—whew! It was like a stab in the chest. These things are so much more hurtful than I realized before they started happening to me.

Add to that I lost all my friends, I lost my home, I didn’t have a record deal, I’d just been broken up with… the city quickly became my hell. So that’s why I’m leaving.

Understandable.

The thing I would tell anybody, wherever you live: if you have friends, keep them close. Without friends around, you’re lost. You’re totally lost.

Going back to early Girls days—how did you and JR White fall in with one another?

I was walking in the park one day and Liza, the girl I mentioned before, started yelling at me from across the way. She’s a legend, she’s amazing, and she told me to come to a party that night. And I think that was the first time I met JR. Eventually Liza moved into my place, and we went out for a couple years, and JR was one of her good friends.

She had this other high school bestie, Laura Sutro. You know the Sutro family, like Sutro Tower?

Yeah, and the Sutro Baths.

Yeah, so she was a Sutro. She and Liza were like Paris and Nicole—literally. And JR was going out with Laura.

And is that Laura as in “Laura?”

Yeah. JR was her boyfriend for a while, so he was just always around. And he was a cool guy, really quiet, really very different than the rest of us. He was very stable, hardworking, a chef.

I didn’t know he was a chef.

Yeah, he was a very good chef. He worked at Zuni downtown.

One of the first things I remember about him was that he went on vacation to Japan by himself, for no particular reason. And that was really cool to me. People didn’t do things like that in Texas. He was just a cool guy. As I started to go out with Liza and become more of a fixture in the scene, JR would just always be around. Anytime I would get into some kind of trouble, JR would be there to smash somebody in the face.

That’s basically what he was to me, a caretaker. We’d go out to have a weekend together with friends, and he’d be the guy cooking. He was very protective. He wouldn’t talk a lot, he would listen.

At one point, he needed a place to live, and the room next to mine was available, so he moved in. And he started to hear me in the other room trying to record the songs that would be on the first album on my four track. I’d do a couple takes, and then I’d just turn it off and say, “Fuck, this is shit.” And I think he listened for a couple weeks, and then one day he just came in and said, “You know, I went to audio engineering school. I’ll help you out.”

So we did a little more on the four track together, and then he was like, “If we really wanna do this correctly, we gotta spend some money.” So we spent $600 together to split a reel-to-reel Otari tape machine, and it sounded a lot better. Then we started to make the actual recordings that would be on the record. As those started to turn out better, JR was like, “We could go all the way with this if you wanted to have a band.” So he joined as the bass player, and we changed the name from the original Curls.

Right, it was Curls first, and then it became Girls.

Yeah. That was his idea, he came up with Girls. I’d made all the artwork already, and it was very literal. If I was writing about a certain girl, I would take her picture and make it the cover art, as if we were making records. He looked at the aesthetic I’d come up with, and he was like, “We should just call it Girls.” And I liked it because it still sounded like Curls. So we went with that.

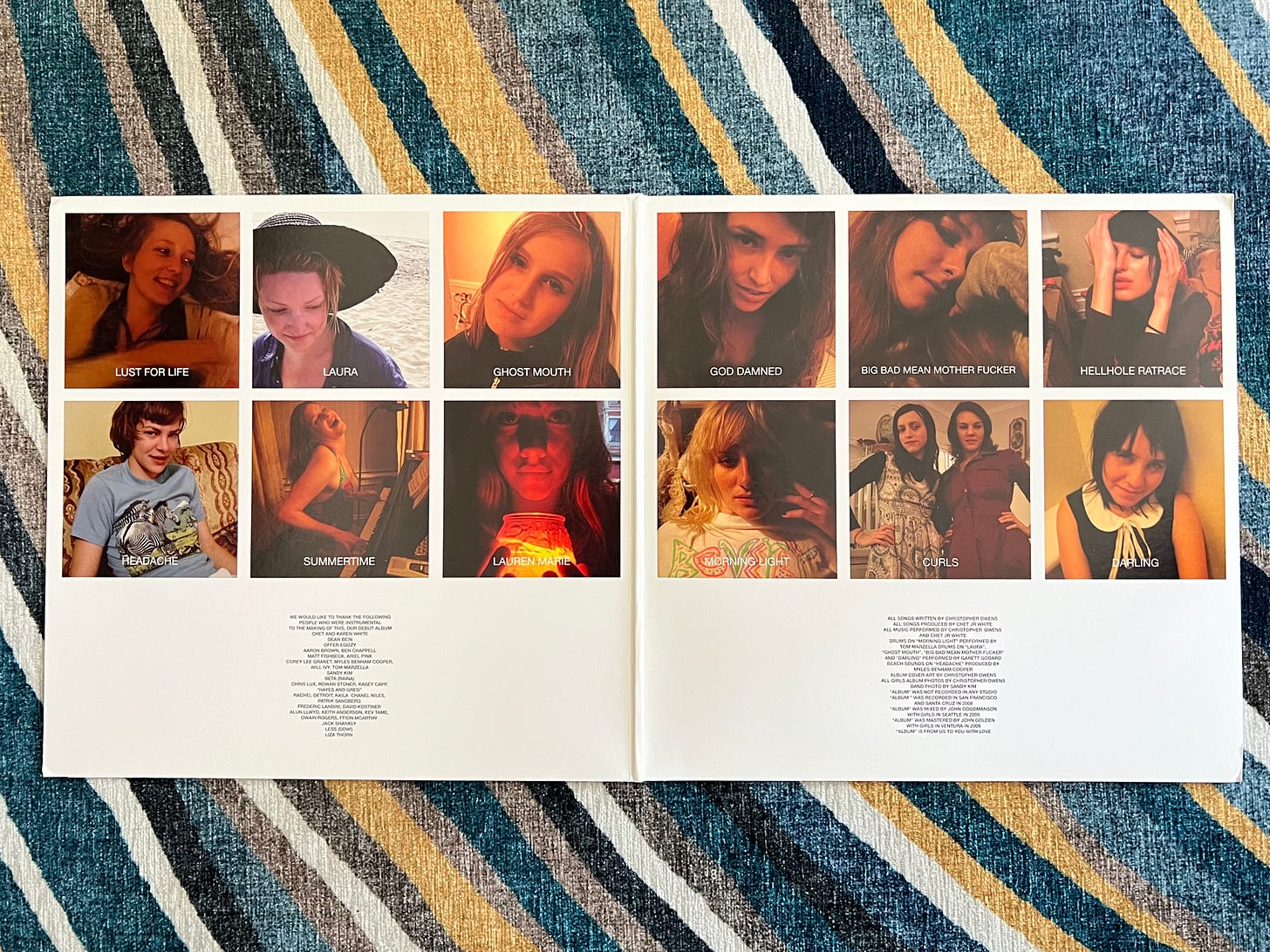

On the gatefold of the first record, every song has a corresponding girl in a square photo, with the title beneath each.

Like 7” covers.

Yeah, I’ve got the “Lust for Life” 7”, and I’ve got the “Hellhold Ratrace” 10”.

Yeah. I just finished the rest of them as if they were all singles, what they would look like.

The way everything looked, the cohesiveness of it all—it was perfect.

Yeah. People had different ideas about what the photos were. They were like, “Who are all these girls?” And they were surprised when I was like, “These are all my best friends.”

It seemed so clear that it was just people in your life, people you loved.

Yeah.

So you and JR just kinda fell into working together.

Yeah. We lived next to each other, he had a background in it, and we wanted to do it. I was determined to get it done, but if he hadn’t stepped in, I don’t know how it would have turned out. I was already playing with Holy Shit, so Ariel was talking about doing it for a little while. It could’ve turned out to be a totally different thing. But JR wanted to do it, and he could do it.

So you guys did it.

I mean, we never even talked about “doing it.” We never thought about playing shows, or a record deal. Our goal was to put the songs on MySpace and have people like them. From there, people thought, “Oh, it’s a band, because there’s a MySpace page.”

And it was just the two of you the whole time.

Yeah. When we booked our first show, we just reached out to other guys from other bands that we knew here to play with us.

And did they become part of the original lineup? I know John Anderson was in the band for a while.

No, John was from LA. He came later, and we wanted him to stay, but it didn’t work out for him. But in my mind, John is one of the core members. He was the only person who joined to actually be a part of the band. Everybody else was somebody in a band that we knew, and we’d ask them, “Can you just play this show?” And none of them would stay permanently. John was the only one.

Where was your first show?

It was at Cafe du Nord. Sold-out mania. The first show was as good as any show we ever played. It was amazing.

I can imagine. Was that 2008?

Yeah, must’ve been. It could’ve even been 2007, but I’m not sure. I should know that, but I don’t.

Dates are dates, it is what it is. So you put the record together in a studio—

No, we just kept making tracks for MySpace.

Just individual songs, and then eventually they became the record?

Once we signed our deal, then we went to finish everything and compile it as an album. We went to Seattle to mix it all at a nice studio. But initially it was just song by song.

And then it came out, and right away it seemed to catch like wildfire.

Yeah. We’d played South by Southwest and done a few tours before there was a record at all. So by the time the record came out, people were ready for it.

Did the way it was received by fans and critics surprise you at all?

I thought people would make fun of the sincerity and earnestness.

The whole point of the songs, the whole point of what we did period, was to make music that mattered. Every band we knew played noise rock, some kind of “cool sound.” That was the agenda. For us, we wanted to make music that people would sing and remember the melody for. We wanted lyrics that meant something.

I would play songs for JR that I liked and be like, “This is what I wanna write like. This is the point for me.” We bonded over the Op Ivy album Energy. Every generation goes out and buys that record because it’s just one of the records you have to have. You listen to that and it’s kids singing about unity in a basement. They’re earnest as hell. You could make fun of that record too.

I thought we were gonna make beautiful music, and I could gauge from the reaction that people got it and were responding the way we wanted. But critically, to be honest with you—I’m jumping around here a bit—but I’d never heard of Pitchfork in my life.

[Laughs]

Those were the people that I thought would’ve made fun of the album. So the fact that all those types also loved it was a surprise for me. I thought they’d call us names or something.

Right. “Look how lame these guys are, they actually care about something.”

Not lame, but like whiny or emo. I didn’t care, we just weren’t expecting everyone to love it. I thought certain people that understood us as people—close friends—would love it. I just wanted Ariel and Matt Fishbeck to love it.

When we started to play shows, and we’d meet the fans, the actual kids, that made total sense. I didn’t have a mind for it, I couldn’t imagine. But when I would go meet them outside and sign their records, it was like, “Yeah, these are my people.” I remember these kids from being a punk in Amarillo in the middle of nowhere.

Right, you were one of these kids.

Yeah. I remember I had this really good friend. She was really cool, she had a band herself, she was a very hip girl. One time she was looking on her MySpace and pulling up fans of hers and making fun of them, like, “Look at her hair, look at that t-shirt.” And no lie, it was just me and her, and I was like, “How dare you?” These were kids that were sitting in some shit town wanting to slash their fucking wrists because they hate their parents, they hate their school, they hate their lives, and they were looking at us on the internet dreaming of one day, maybe, getting to that level. We’re their goal, and you’re sitting here making fun of them?

So when I met those kids, I knew we were doing something right. I never wanted the fanbase to change from that. Obviously, it wasn’t just the kids—there were sensible older people that liked the music too. But the fact that that was our scene, I knew we were doing something right. So it was a surprise, but it was also a confirmation.

And it just felt really good, y’know? To be able to go tour, it was a dream come true—a dream that I never knew I had. I had it an abstract way, like, “One day I want people to like me.” But I didn’t know what that really meant. I never had rockstar posters on my wall when I was a kid. I didn’t understand that.

It wasn’t something you were working towards or dreaming of from a young age.

Yeah, I just didn’t know about it.

Was any of that difficult for you? All the attention, people talking online, all of the expectations?

Not much, no. Nobody really talked shit online. The only times anybody has, I’ve talked to them and they’ve been like, “I’m sorry, I was wrong.” I’ve never been dragged online, I was never a name in the Me Too thing, it just doesn’t happen. I had a friend be like, “Aren’t you scared?” And I was like, “No buddy, I’m not scared.” [Laughs] I don’t do weird shit.

The things that bummed me out were not being able to have the band that we wanted to have, and eventually feeling like I got taken advantage of by label and management people. I thought they were my really good friends. And it was very easy for them to just be like, “Bye.”

But there was nothing really that bad. It was really only stuff between individuals. And I don’t really like to get into that because I don’t ever want to be a VH1 episode of Behind the Music. I want people to remember Girls as the phenomenon that it was, just a perfect thing. In that way, I’m glad that it never turned into shit during the split. We never aired our dirty laundry.

The problems were just things that anybody is gonna go through. It’s nothing new. Everybody knows about these things. JR and I always stayed really close friends, I think that’s something that people don’t understand.

You two stayed in touch after the band?

Oh yeah. There was never a falling out. It was just time to move on for me. And for him too. He just wasn’t in a position to do what I did.

Right. He wasn’t gonna go out and have his own solo career.

Yeah. He really wanted to be a studio guy, a studio producer. And I wish he could’ve gotten there.

He produced a couple great records after Girls. He did one of the Cass McCombs records, and Tobias Jesso Jr.’s record was great.

Yeah. But all in all it was a fantastic experience. It was much better than anything that we’d hoped to come from it.

For me, the ultimate success of it is like, it got done. Those records are there. To me, no matter what happens in the future, it’s ok.

That’s always there.

Yeah. The legacy is there forever. I’m very happy about that.

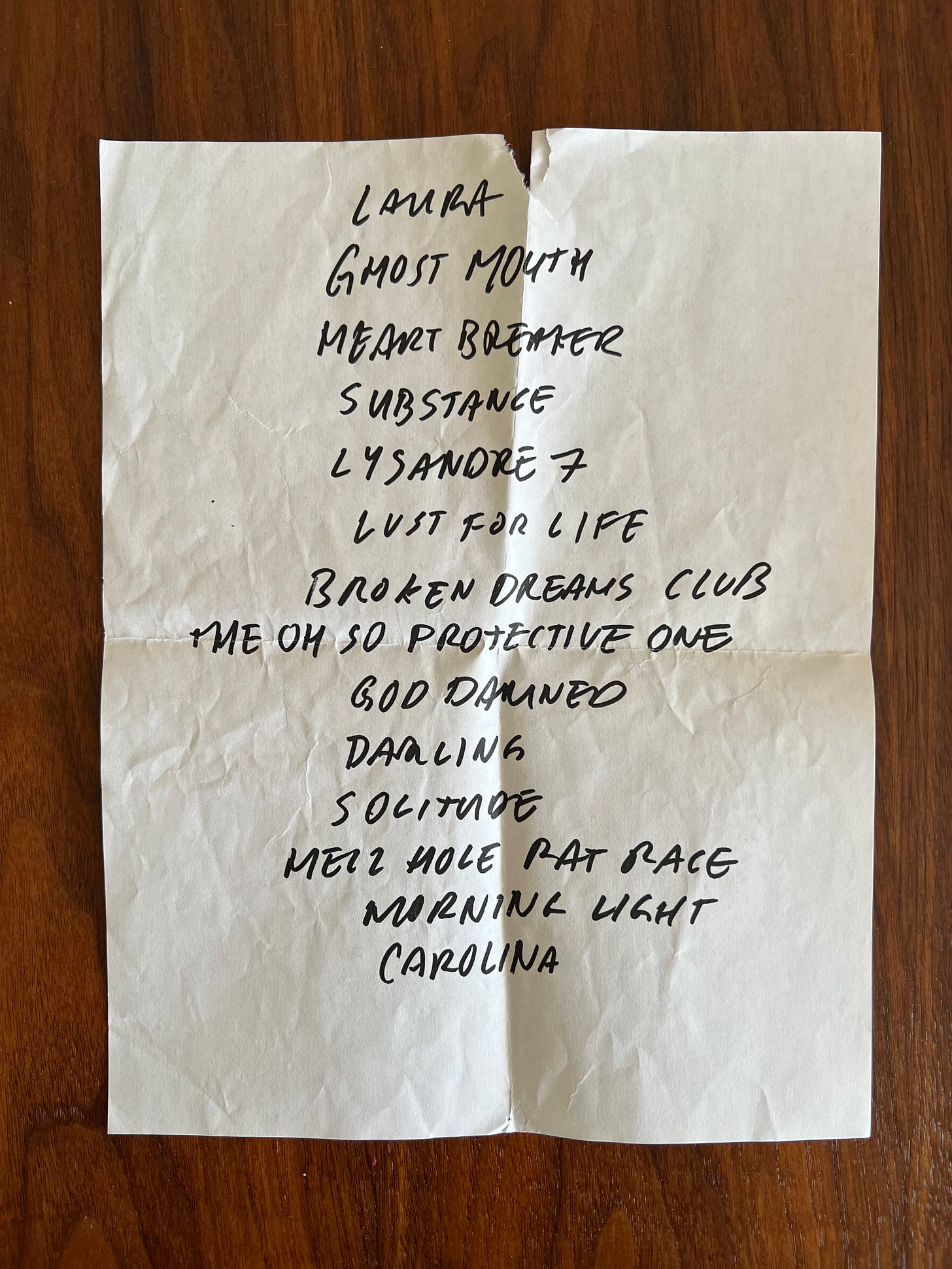

So Album just kinda happened eventually after you put together enough songs you’d recorded for MySpace. But Broken Dreams Club was your first post-break record: after your name is out there, after people have expectations.

Yeah, it was after the first round of tours. After the first European tour and festival tour.

And it was out just a year after Album.

Yeah. We didn’t wanna only play the record on tours, because that’s boring. So we added in six other songs, the next songs I had written. We were playing them live, so we just wanted to do those because people started to know them, and they were ready. It was an EP, but it was longer than an EP.

“Carolina” alone is like seven minutes.

Yeah. The reason I called Father Son Holy Ghost “Record 3” is because I really wanted people to think of them as three equal records: Album, Broken Dreams Club, and Father Son Holy Ghost.

I always wondered why Broken Dreams Club was an EP, but if it’s just the songs that you guys knew and were playing live and were ready to go, that makes perfect sense.

We also had tours coming up. We only had a bit of time. The label was doing our schedule. They were like, “Well, you’ve got this little bit of time. Why don’t you go do an EP?” And I was like, “Ok.” And I think they were expecting like four songs. And we did more.

On a sonic level, you go in so many different directions on Broken Dreams Club. Going from “Thee Oh So Protective One” to “Heartbreaker” to the title track—just that three song run, you’re in three completely different quadrants. And then “Carolina” is like a whole new world.

You think it’s more varied than Album? I feel like we did that on everything.

You did, but I was just listening to Broken Dreams Club earlier today and it sounded so complete. I think that’s my favorite record of the three, because it’s just so brief and so perfect. There isn’t a misplaced second—not to say that there is on Album or Father Son Holy Ghost—but BDC is its own unique thing. No one was putting out six song EPs that were that significant. And “Carolina” is like, the one for me.

I love “Carolina.”

I remember seeing you guys at the Fillmore up here, and it was before Broken Dreams Club came out, and I think you closed with “Carolina.” And I’d never heard it before, and it was just like, “Man.”

It was a good song.

I think the main thing that changed with the sound on BDC was the inclusion of the live band. The guys that played on it were the guys touring with us.

There’s a bunch of great studio shots on the inner sleeve of the record—just everyone in the studio hanging out together.

Yeah. And it does affect the sound. On Album, there’s no official drummer. There’s a drummer that comes in here and there, but mostly that’s me playing, like hand drumming. There’s only a couple songs where it’s a full-on drum kit. And they’re different people too, different people on different songs.

So you can really hear the difference with Garret Goddard, the drummer on BDC. You can hear him throughout. That consistency wasn’t there before. He has a certain style, and you can hear it. We had a keyboard player now, too.

Matt Kallman, right?

Yeah. So for me, the difference between Album and BDC is the band. It’s a band record. The first one is more like a recording adventure between two different people.

I can hear the consistency, but it’s interesting that it’s different for you.

I’m just always thrilled to hear how masterful everything sounded a year after Album. JR seemed like he was already in complete control of all his powers in the studio.

Yeah. Except he was totally absent for “Carolina,” which is funny. During the second half he plays on it, but he didn’t even want to play that bass line.

Really!

He played it and I was like, “That’s awesome,” but he didn’t like it. But he did it to be nice.

JJ Wiesler, the guy whose studio we were recording in—that was really a lot of his work. He and I spent a whole day in there recording stuff and then slowing the tape down to half-speed. Like those bells you hear? They’re actually tiny little bells. But when you slow it down they sound big.

They sound like church bells.

Yeah, it was just me and JJ doing that. JR was frustrated with that song. He was just like, “I’m outta here.”

His stamp is really on the first song, “Thee Oh So Protective One.” That was a big deal for him. He really wanted to have trumpets and all that. The trombone player was actually one of my friends from the jazz nights that I was talking about earlier.

That’s fascinating, because “Carolina” is such a huge sound. It’s up there with “Hellhole Ratrace” and “Vomit” and “Forgiveness”—they remind me of Guernica, just these extraordinary panoramas, which always seems like the kind of thing JR would do in the studio.

Yeah, he didn’t know what to do with it. We tried some stuff and it wasn’t working. It was our first time in a studio too, so it was different. JJ had to be there—it was his studio, he’d been hired—and it was a good thing. We were running out of time, and he just took over.

But the majority of the song was something we worked out live, and that was just JR and I putting it together. So it is his sound in a lot of ways, but he knew he didn’t have to deal with it in the studio. He was like, “I’ll come and play bass when you’re ready.”

The title track was the first time we recorded me and a drummer playing live at the same time, because we didn’t wanna have a click track. It’s such an odd song. I kinda stop and go when I sing it, so we just did it live together, and we’d never done that before. There were a lot of cool things like that.

For both JR and I, the exciting thing was being able to say to people like, “We have $300 for you to come play a horn.” So we did that and it was fun. And then JR got more involved in the mixing. I don’t do anything with that stuff. He puts his sound on more at that point.

After the music has been recorded.

Yeah. Because he and I both, we wouldn’t be like, “You have to play like this” to the musicians. We just wanna let them do their thing. We weren’t writing out sheet music. Neither of us ever did that. His sound is more in the mix.

Was Father Son Holy Ghost a similar kind of thing?

No, it was totally different.

How so?

Before we went into it, I was like, “We have to win a Grammy.”

A Grammy?

Yeah, I believed we could win a Grammy. I really believed that. We’d just been touring for a couple years on the two records, and I’d seen all the other bands out there, and I really believed we could win the Grammy for Best New Artist. I believed JR could produce it, I believed in the whole group. And I had so many songs at that point. We picked them out together. Out of like thirty songs, we were like, “These are the ones.”

And at one point JR was like, “I found this guy. He’s won a Grammy before, and he worked on Elliott Smith records.” And I was like, “Cool. Hire him.”

And that was Doug Boehm?

Yeah. And when Doug showed up, it was like he was in charge. And it made sense, he was hired to be. He made us do rehearsals, and were like, “What the fuck? I don’t know what you’re doing man.”

But by the time we actually recorded, I think he understood, “OK, this is how these guys work.” And he worked with us the way we would normally work. JR picked out the studio to work in, it was in the Tenderloin. Not a professional studio, just somebody’s private thing they’d built, with a lot of really cool gear. And Doug was the main producer on it.

There was a lot of back-and-forth between him and JR working out where to go. For me, it was kinda the same, business-as-usual. But a whole other wildcard was our new drummer, Darren Weiss. He was just a level of amazing that we hadn’t ever had.

I loved playing with Garrett, his looseness. When I listen to Broken Dreams Club, I love his drumming, there’s just a certain sound. But Darren would write everything out in a notebook…

Tight, professional…

Yeah. And that was his personality, too. So when you add him in there, and then we’d never recorded with John Anderson—that was a whole other beast. I think he quit like six separate times, but Doug would always get him back in.

It was just a lot of new people together for the first time. It was crazy. But it sounds the way it does because John is that epic. And Darren’s drumming is that epic. And we had fucking Danny Eisenberg, who I’d play a lot with later—an amazing keyboard player. We put him on twice the number of songs we’d planned. And we didn’t tell him what to play either, that was all him. It was just a lot of amazing people.

And Doug kept us on track. He would be like, “No, JR, we’re not putting a microphone in the bathroom just to ‘hear how it sounds.’ We’re just gonna do it this way.” And JR would be like, “OK.”

I remember afterwards JR was like, “I remembered a lot of what I learned in engineering school from working with Doug. There’s a reason why you learn those things.” You learn what gets the best results in school, and that’s what Doug was doing. And when you listen to Tobias’s record, there’s no microphone-in-the-toilet shit. It’s all straightforward.

It’s a very classical sound.

I think it was important for JR to have that experience. But he hired him. And I think that was an adventure for him, having somebody else who was just like, “No, we’re not gonna do that.” They would get edgy at points, but they worked it out. And Doug is still a friend today. He and JR never had a falling out either. But the musicians on Father Son Holy Ghost are what make it what it is. Doug just played it classic, made it sound good. The musicians are what make it amazing. And the songs—the songs and the musicians.

The only other thing about FSHG that was significantly different was the backup vocals. I wanted a certain gospel sound.

It really reminds me, as someone who’s done a Bob Dylan podcast for a couple years, of the sound he got during the Christian era on Slow Train Coming and Saved. It’s the same exact kind of feeling that you get from that music.

Yeah. And some people say Pink Floyd. But I didn’t have any specific people in mind. Doug knew those girls from LA and brought them in.

And they were the ones that would go on to tour with you.

Yeah. That was a gamechanger when people heard that. When “Vomit” came out, that was what was written about. Like, “Oh my god, and then these girls come in!” And at the shows when they’d sing—it was a huge deal.

The people that were playing with us at that point were all really amazing and helped make it sound really really great. Unfortunately, John quit by the end of the recording sessions. But then Darren was like, “My brother plays guitar.” And two weeks later Evan Weiss was in there playing. He could play all three records.

Just like that [snaps fingers].

Yeah. He was amazing.

We only had really good experiences with everybody we played with. I just wish we could’ve had our own band. Like, even Darren had his own project. Everybody we played with was already doing something else, or wanting to do something else. It wasn’t like it was with JR and me, where it was the only thing we were doing. When you have that, you have so much more growth as a band. You’re not starting from square one every tour.

The record came out in fall 2011, just another year after Broken Dreams Club. And then you guys toured until the spring. Primavera was one of your last shows, right?

Yeah.

And then in June, or sometime in the summer, you just called it.

Yeah. John wasn’t a part of it anymore, JR expressed wanting to make some lineup changes, and Darren was leaving to do his new band. And I was like, “I’m tired of this shit.” I didn’t wanna be teaching somebody how to be playing “Lust For Life” again.

It just felt like I was trying to force something that wasn’t happening And I don’t wanna speak too much for other people, but JR didn’t really enjoy being on the road very much. He didn’t enjoy the traveling. And I knew he could not only be happy, but like—he should’ve been in a studio with new bands every month, y’know? So I thought that was what we’d go do. I’d go have a solo career, and he would do that.

I think Girls just had run its time. And we didn’t wanna be forty or fifty years old with a band called “Girls” putting out songs with girls’ names. That’s for kids. It was time for me to do something else.

A lot of the bands from that era are doing ten and fifteen-year reunion tours. Do you have any sort of interest in that with the Girls material?

That’ll never happen. Even when JR was still with us, we both would’ve said never. But especially now. I would never do that with anybody else.

I still play the songs. I don’t know if people have seen solo shows, but they’re my songs, and I still play them. And I’ve had tours where John was there, Danny Eisenberg was there. I had the actual FSHG lineup, except for the drummer and JR. And it sounded amazing. So people can hear the songs. It just won’t be billed as a “Girls” thing. There’s no need to do it. It wouldn’t be anything different than what I already do.

That kind of stuff is a little played out. Sometimes it’s great, sometimes it’s nice to see. But only if those people aren’t really playing. If they’re already playing in some other fashion, you might as well go see that.

Agreed. And it needs to be worth it, as far as I’m concerned. If it’s just a random album that came out in 2011, it’s like who gives a shit.

[Laughs] Yeah.

After the band you went right back in the studio and cut Lysandre, and that was out about a year after FSHG came out. That was a really different sound and vibe. I was just listening to it last night for the first time in a while, and it sounds amazing.

Yeah, it does. I can’t find a problem with it. I’m really really proud of that record.

It’s an absolute delight.

For me, it’s a major achievement. It’s all in one key so the interlude can play in between everything. It was basically like writing an entire album at once. It was a challenge, and I feel like it was really well done.

I still remember, I came up from Los Angeles around that time to see you play the album for the first time in a theater up here.

Yeah! Did you see that show?

Yeah, I still have the program from that show.

How did you like it? Was that show good?

It was amazing. There was a set behind you guys, everyone was all done up in these beautiful outfits.

The set existed there already.

Sure, but I didn’t know that!

Yeah, we picked it for that.

What was so great about Girls was every year, with every record, you topped yourself—again and again. And with Lysandre, it seemed like you were doing it again.

Yeah. Except the status quo hated it. For whatever reason it wasn’t “cool.”

I didn’t expect it to be as well liked. But I didn’t expect people to go out of their way to pan it either. Certain websites were making fun of my hair on the cover. It’s like, that’s your comment on the record? It was so ridiculous. You’re supposed to be the premium music journalism outfit? Gimme a break. Adults were telling me to get my hair out of my face when I was like ten years old. You’re officially a square if you’re telling people to get their hair out of their face.

Lysandre was a really happy-sounding record. It doesn’t have that same level of tortured ripping-your-heart-out-of-your-chest feeling that so much of the Girls stuff had. I was thinking about it, and I came to the conclusion that people in the music industry at that time were expecting one particular type of thing from Christopher Owens.

Yeah, some shoegazing-sounding thing…

Shoegazing-sounding, and songs like “My Ma” and “Vomit” and “Substance.” And so for you to be doing something new and different and unfamiliar to people…

Yeah. But I mean, “Part of Me” is an amazing song.

Of course!

There’s amazing songs on there. There were songs that we used to play as Girls that people loved on there. But I met hundreds and hundreds of kids that loved that album, so I don’t care. I just wish people would’ve taken it seriously.

That was an eye-opening experience, to see how much of an agenda there is. I even talked to this journalist that I was interviewed by so many times, and I was like, “I don’t understand the criticism from certain corners.” And he was like, “They’re fairweather friends, buddy.” And I was like, “Yeah. That’s very true.”

That record is about the first tour that Girls did. And then this amazing thing happens where I meet this girl, and I wasn’t expecting it, and it becomes romantically charged, the gem of the thing inside the story. So I titled it after her. But then, by the end of the record, it’s an acknowledgement that those things come and go—like, “a part of me is gone.”

I did that specifically as a commentary on the whole Girls experience. It’s about the first Girls tour, but it’s also about Girls. And nobody even tried to see that. I was making a really profound statement on what had happened, and nobody even thought twice about it. So it was interesting to see.

I remember feeling kind of pushed under the rug, but it also sorta toughened me up. I’d only had good comments from people before that, so I didn’t wanna be too sensitive about it. I just had to be like, “Ok, people don’t like it.” But to have that keep happening was weird for me.

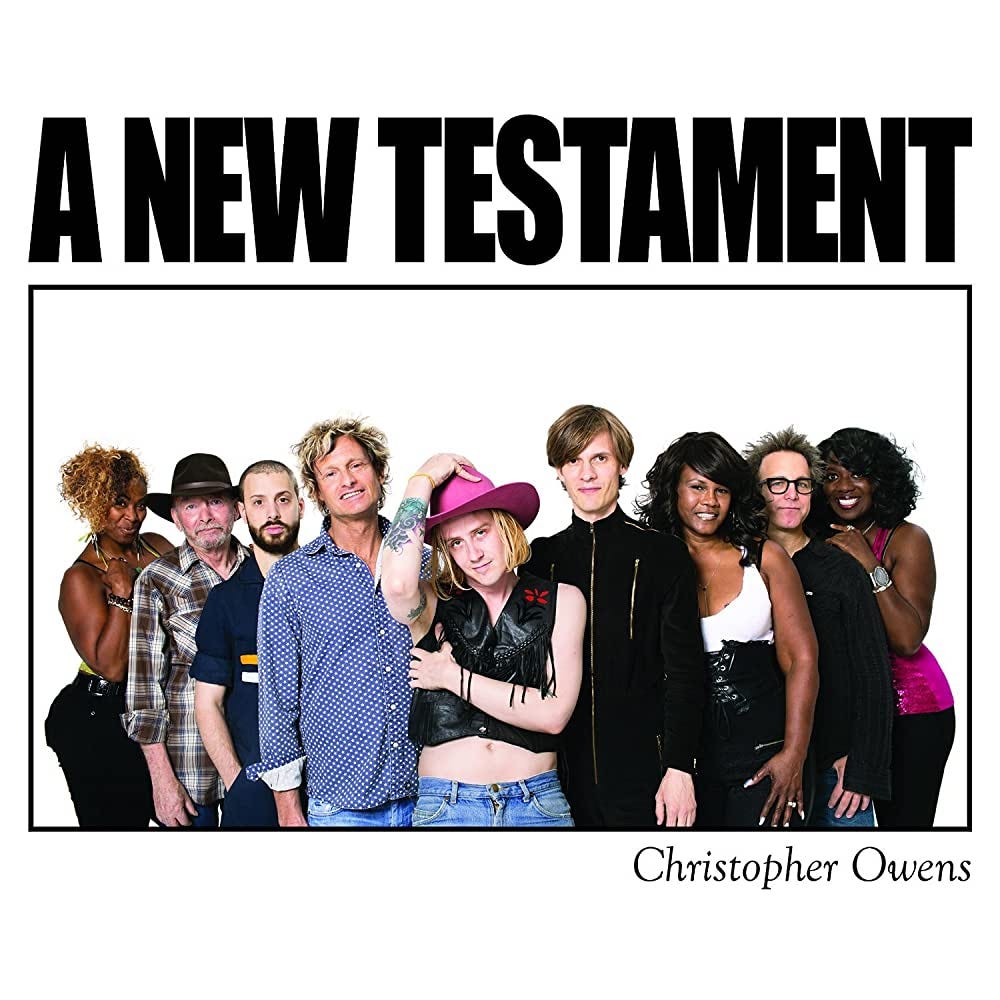

Right. You put out A New Testament a year after that, which is also a fantastic record.

Yeah. I stand by it though. I don’t give a fuck. I love every record.

I think both of those records are fantastic.

I think plenty of people do too.

It may just be a silver lining, but I think over time they’re going to be looked at more fondly.

Yeah, you’re right. I’ve always said that to myself too. There’s a bigger picture that you can’t really see from here. I think people don’t understand that I just wasn’t cut out to like…

Do the same thing, to crank it out.

Yeah. You can hear that on the first record. The first thing that people wrote about was like, “This is awesome, these guys just do whatever they want.” It’s like, hello, I’m still doing that! I don’t think it should’ve been such a surprise.

To me it wasn’t. To go from FSHG, this classical Grammy-sounding record, to Lysandre, to A New Testament, in two years—that’s extraordinary. I just wish more people had seen it at the time.

Yeah. Hopefully if I can get back to work soon and have records that people like and keep going, I don’t think people will really pay attention to how much certain records were or weren’t liked. It just kinda goes away. It’s hard to go through while it’s happening. But it goes away. It becomes meaningless. Whereas the things that people do like, those’ll always be there. That doesn’t go away.

Nobody wants to go through that shit, but at the same time I think if I was throwing a fit about it and being like, “I’m not gonna play anymore, these people don’t deserve it,” then I wouldn’t really be mature enough to be deserving of the attention, to do this at all.

That’s really gracious of you.

It’s true, y’know?

I agree with you, but I feel like there are people that’ve gone through similar things and don’t have that same opinion.

I have a lot of friends that are like, on the verge of doing big things. And they’ll tell me, “I don’t know why people didn’t like what I did here or there.” And it’s really hard for me, because I want them to have success, and I don’t know why it didn’t hit. So I don’t know what to say. But it shouldn’t stop you, and it shouldn’t stop me. You just gotta keep on trying.

I think the pandemic was harder than that stuff, y’know? Just not being able to do it at all.

Yeah, I mean for a live musician, especially for someone who obviously feeds off the energy of those around you…

Yeah. I was out playing guitar on the sidewalks just because I had to play.

I saw you outside of Zeitgeist at one point. I almost came up to you and I didn’t because I was embarrassed.

Outside of Zeitgeist, huh? Playing or just standing there?

You had your guitar, and you were like halfway playing, walking around.

Oh, I was walking. Ok, yeah.

I would play for hours in between Dolores Park and 18th, by Bi-Rite. Right there there’s really good traffic. It’s my favorite spot. I play inside this garage. They let me, nobody complains there.

No one should complain, they’ve got Christopher Owens playing live for them in the city of San Francisco!

[Laughs] Right. But these people, they have no idea. So I’m expecting like, “Oh, can you move?” But they come down and give me money. They like it.

That’s the least they can do.

That was nice, just to get more guitar playing.

Sure, keep your fingers busy.

I got better too. I’ve always relied a lot on the other guitarists to get things done, but I feel like now I can do more. We’ll see. We’ll see what happens.

You’ve been more than gracious with your time here tonight. Thanks so much, Chris.

Thank you.

Be well.

This was such a beautiful interview. Thank you.

Fantastic interview. Makes me want to go back and listen to all the records. I slept on Lysandre but loved a new testament and all the Girls records. Lysandre will be up first.